A Goat, a Calf or a Sheep. The Dilemmas of a Contemporary Copyist

29 October 2018

Making a whole copy of a parchment leaf of a manuscript or a document always poses a dilemma: what parchment use so that it shows closest resemblance to the original?

I have been invited by National Museum, Kraków to make copies of different documents as a part of ‘The Past for the Future. Renovation and Equipping of the Czartoryski Museum – the National Museum, Kraków to dispaly the unique collection’ project.

During my first visit in the Czartoryski Library where all those “ordered” manuscripts are kept I began my reserach with the inspection of the material they were made from. I decided to choose the proper parchment by comparing the original ones with the parchments available on the market. “Easy task”, this is at least what I initially thought, “I will compare, choose and order the right one”.

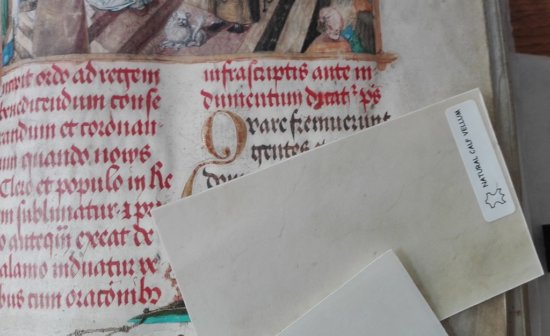

Comparing the parchment samples with Erazm Ciołek’s Pontifical. Photo Barbara Bodziony

Having worked with parchment for ten years now I have built up quite an extensive collection of various samples. Many of them are but little scraps, yet enormously diverse ones. They come from French, English and Polish producers. As it turned out, among hundreds of samples in my collection there was not a single one that would match the original. When the colour was right, the thinkness was not. When I matched the thickness, the texture did not match. Stalemate.

parchment & vellum samples Photo Barbara Bodziony

Let us begin at the beginning then. A parchment leaf is made from the split skin of an animal (usually goat, sheep or cow). Firstly, determinig what animal skin was used in the original manuscripts was the task I found too difficult to perform. Sometimes it can be done judging by the look of the skin itself (present-day goatskin parchment, for instance, often has clearly marked pores after hair follicles), often however it is a task impossible to complete, especially by someone who does not produce parchment, but only work with it. In my research I decided to turn to an expert. And since the world probably knows no better parchment producer than William Cowley, I grabbed the phone and dialed the number of William Cowley company, England.

The call itself turned out to be a very instructive one. Never before had I had such a lengthy and in-depth conversation about parchment, discussing issues I had no idea existed. I admit that with a promise of excellent beer I even tried to entice Mr Paul Wright, the general manager, into coming to Kraków and examining the documents, for could an Englishman resist good beer? Unfortunately he was too busy to accept my invitation, though he found it tempting indeed. All had to be done by phone and mail then. Mr Wright drew my attention to one of the crucial factors in matching parchment. In England if a commissioner was a king or aristocracy member the material was of highest quality, meaning calfskin vellum. The conlcusion: who the comissioner was could determine the choice of skin type.

But still, was a choice of skin depanding on the animal itself or perhaps of a skin quality, irrespective of the animal? I will broach the subject later.Basically medieval and later craftsmen could choose between calfskin, goatskin or sheep skin. Those were the skin types they could purchase from parchment makers.

Parchment sellers, University Library, Bologne. Scrolls of parchment in a contemporary parchment producer’s storehouse

The latter ones used to specialize in making one skin type. We know, for instance, that most of Bolognese parchments were made of goatskin, whereas the Parisian ones of calfskin or sheep skin. The choice of a proper skin depended on a few factors. Firstly, on the book or document size, the biggest leaves could be obtained from calfskin. That is why a scribe who was about to make a big choral music book would rather look for a vellum. Secondly, it was important whether a book would be a simple textbook for a 14th century Parisian student or a luxurious prayerbook for a prominent personage. A textbook did not have to be made of the best quality and most expensive material, but the commission for a bishop of Paris required the highest quality parchment. The number of illuminations was also of considerable importance, for they required good quality material. Thus it was a matter of money as well. If a commissioner wanted a book to be at its richest, he would pick the most valued delikate skins, thin and pure white. Such skins were used for making small luxurious prayer books popular in the late Middle Ages.

The Book of Hours of Claude de France (MS M. 1166). Photo courtesy of Schecter Lee

The first three documents for the National Museum I was to copy were the manuscripts made in the key moments of history or for the prominent personages. The savings on the price of parchment were out of question here.

One of the manuscripts was associated with Erazm Ciołek, the bishop of Płock and secretary of King Alexander I Jagiellon. Another one, not medieval, but made from parchment, with Prince Władysław Czartoryski, the founder of the Czartoryski Museum, Kraków.

The third one was the Deed of the Prussian Homage of 1525, including a treaty between King Zygmunt I the Old and Albrecht Hohenzollern, the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights. To put it briefly, these were the luxurious products made for the exclusive clientele. And such a parchment I decided to purchase for my copies.

I provided samples of parchments determining the three features of each of the original ones: thickness, colour and smoothness. Hoping to find similar products I sent the samples with the descriptions to the two producers, one in England and one in France.

Parchment samples Photo Barbara Bodziony

Getting back to the subject of parchment quality, I would like to mention very interesting research results published in 2015. The reserchers studied the well known case of strikingly smooth and white parchment leaves of the 13th century bibles astounding in their thinness.

Fot. www.smu.edu, Biblia, Paryż ok. 1250, Bridwell Library, BRMS 6

Some of the reserachers claimed that such a quality could have been obtained only from the skins of the fetal animals or very small ones (e.g. rabbits). Already Daniel V. Thompson refuted this theory, but, as we know, it was repeated in many texts on the subject over and over again. In 2015 team of researchers studied more than five hundred manuscripts, including a group of seventy two thirteenth century bibles. Suprising results were received. Proteins obtained by using modern noninvasive method of peptide fingerprinting were subjected to examination.

Collecting parchment sample. Photo courtesy of Davyd Keyes

It showed that 68% of bibles were made from vellum, 6% from mature sheep and 26% from mature goats. As it turned out, the craftsmen of the period (the research concerned books made c. 1220-1300) reached perfection in producing astonishingly thin parchment, using not the skins of fetal animals, but ordinary big skins of maturing ones. It demanded finest craftsmanship and skill to define precisely the amount of time needed for bathing the material in lime water and after it was rinsed out, stretched on the wooden frame and dried polishing it.

Parchment makers at work. Left: Christoph Weigel, Standebuch, 1678 Right: William Cowley worker. The technique has remained unchanged.

This leads to the conclusion that a high quality product of a desired thinness could be made thanks to treatment skills performed on many types of skins, which means that determining what animal skin was used in the process is not always possible.

And I haven’t determined whether the original documents I worked with were made from calfskin, goatskin or sheep skin. Regardlessly, the producers have provided me with excellent parchment, which I have used for making copies. But more on the subject next time…

Bibliography

Daniel V. Thompson, The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting, 1956

article about the research from 2015: https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/112/49/15066.full.pdf

back

back

Comments: